Find all our Student Opinion questions here.

Have you ever heard two songs that sound remarkably similar? What about watched movies or read books with similar plot points or characters? Do you think there are instances when it is O.K. for artists to borrow from each other? Should there be consequences for artists to borrow too much?

In “It’s Got a Great Beat, and You Can File a Lawsuit to It,” Jon Caramanica writes about musical artists who have faced lawsuits for musical connections that are, in Mr. Caramanica’s words, “flimsy at best”:

Occasionally, pop innovates in a hard stylistic jolt, or an outlier comes to rapid prominence (see: Lil Nas X), but more often, it moves as a kind of unconscious collective. An evolutionary step is rarely the product of one person working in isolation; it is one brick added atop hundreds of others.

Originality is a con: Pop music history is the history of near overlap. Ideas rarely emerge in complete isolation. In studios around the world, performers, producers and songwriters are all trying to innovate just one step beyond where music currently is, working from the same component parts. It shouldn’t be a surprise when some of what they come up with sounds similar — and also like what came before.

The idea that this might be actionable is the new twist. Every song benefits from what preceded it, whether it’s a melodic idea, a lyrical motif, a sung rhythm, a drum texture. A forensic analysis of any song would find all sorts of pre-existing DNA.

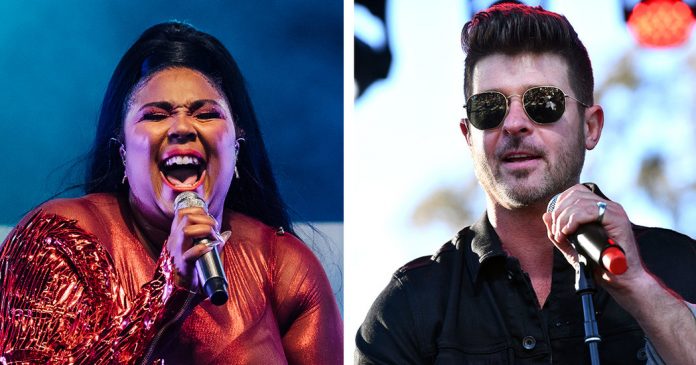

A copyright troll exploits that, turning inevitable influence into ungenerous and often highly frivolous litigation. And given how lucrative the “Blurred Lines” judgment proved to be, it has become a de facto blueprint for how claims about originality will be litigated moving forward: If there is a whiff of potential borrowing on a song (and there almost always is), the borrowed might come knocking.

This forecloses on the possibility that there is some value in copying, or duplicative ideas. It also suggests that all copying is alike — the brutally unethical kind, and also the Leibniz-Newton kind. It fails to make a distinction between theft and echo, or worse, presumes that all echo is theft. It ignores that the long continuum of pop revisits sonic approaches, melodies, beats and chord progressions time and again. It demands that each song be wholly distinct from everything that preceded it, an absurd and ultimately unenforceable dictate.

Mr. Caramanica goes on to say:

The idea that there is a determinable origin point where a sonic idea was born is a romantic one. But a song is much more than romance these days — it is an asset, and a perpetual one at that. Note the recent boom market in the rights to song royalties. Check out the listings on royaltyexchange.com, where you can bid on fractional ownership to the rights for thousands of songs. Or the catalog gorging happening in the music publishing sector, with firms like Kobalt and Merck Mercuriadis amassing huge catalogs. Strategies like these are the equivalent of placing bets on every square on the roulette table. A fractional claim (via songwriting or sample credit) on a pop megahit can mean millions of dollars.

This system encourages bad-faith, long-shot action. Juries filled with non-music experts are ill-suited to make decisions in cases that tend to come down to the testimony of dueling musicologists. Perhaps a better solution is needed: an arbitration panel, with buy-in from all the major record labels and song publishers, where claims can be adjudicated by a jury of peers.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

Do you think it is possible to identify an original creator of a musical sound or style? What elements of a song (lyrics, beat, melody, etc.) do you think a songwriter, producer or musician can claim ownership of?

How do you distinguish between borrowing, influencing and stealing? Do you think there is an easy way to determine how an artist incorporates music they have heard before into their own work? Do you think it is possible to create purely original work?

Do you listen to any musicians who have been accused of stealing from another musician? Does this change how you view or interact with their work?

In the article, Mr. Caramanica suggests that having an arbitration panel of musical peers would be better than having jurors who are not musicians determine the fate of pop music lawsuits. What do you think? Do you think that experts in the music world are better suited to make these decisions? Why or why not?

Can you think of examples of songs or other forms of art that borrow from already created works? Do you think this is more widely accepted or embraced in one form of art versus another?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.